A few weeks ago I went to Glasgow.

On our first day we walked to the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, pushing through a grey morning in a city that wore it like an old jumper as the rain flickered happily in the air.

I’d never heard of the Glasgow Boys– a group of anti-establishment painters, active in the late 1800s– but an exhibition of their work provided me with a whistle stop tour. Many of the pieces felt tailor made for a sentimental softie such as myself, with sensitive evocations of impossible rural scenes, whispered on to the canvases. They made me think of Thomas Hardy, another favourite of mine who conjured up an imagined past and set about defending it from corruption with vigour.

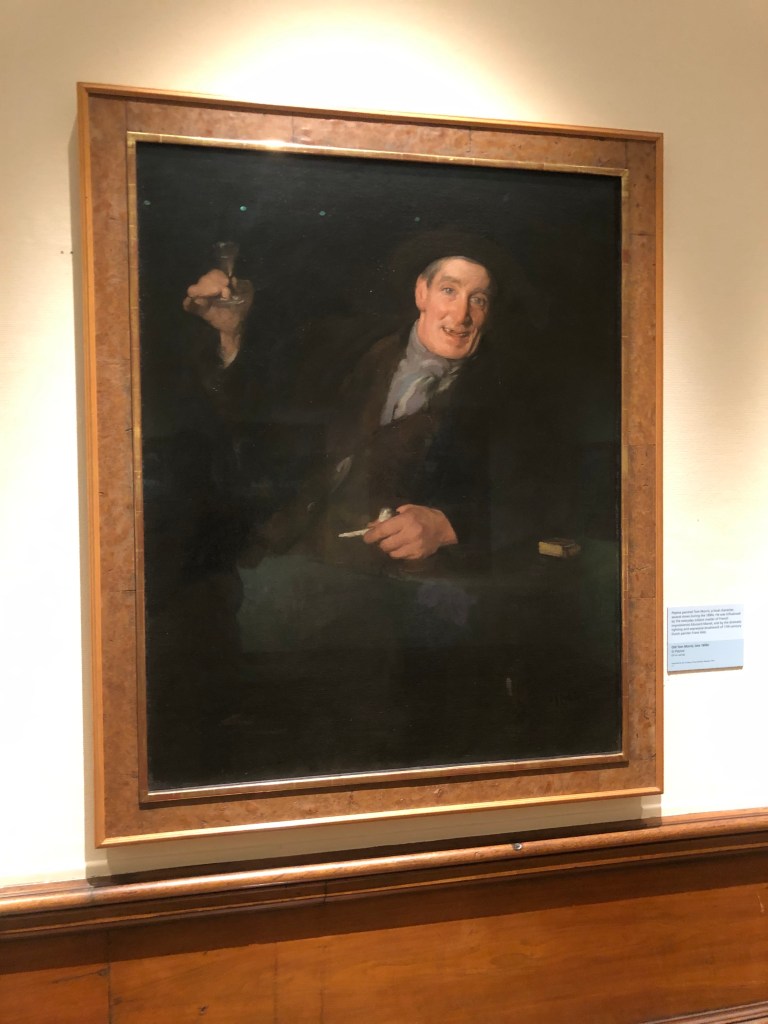

But the painting that struck me the most was not an idyllic landscape but a portrait. Emerging from a dark sea of paint, that barely hints at a room, is the bright face of Old Tom Morris, who leans on a wooden table and raises a dainty glass to us. The placard tells us that Tom Morris is a ‘local character’ who the artist, S.J. Peploe, painted multiple times. I think the term local character is brilliantly provocative– it animates the mischief and vitality that Peploe had encased in Tom’s frozen expression.

I think the incredible lightness of his portrayal is not only an attempt to reflect his nature but also a philosophical point being made by the artist. Tom represents the veracity of (then-) modern life that fascinated and inspired many of the Glasgow Boys and he is presented as the antidote to the artifice of academic painting of the time. In the wake of his smile, we feel the warmth of chatter down the local and the joy of our friends’ idiosyncrasies. It is a memorial not only to Old Tom Morris, but to the weightlessness afforded by sincerity and the sharp crunch of gravel on the walk home.

With this in mind, as I walked away from Tom’s radiance, I was reminded of a more recent phenomenon that seeks out an unfiltered reality. On TikTok and YouTube and Instagram there are thousands of videos of people featuring ‘ordinary’, often vulnerable, individuals as the basis of their content. Most recently, I have seen videos of street photographers approaching homeless people to take their portrait.

On the one hand, it can seem fairly harmless, or even positive. We can cut through the sanctimonious, hateful bullshit of the media and the widespread ignorance of the social internet and be placed face-(to-screen)-to-face with a person, rather than a contrived and deliberately divisive caricature. They are made real for those who might otherwise dismiss them as an inconvenient and distant artefact. Their humanity is insisted upon and their dehumanisation made much harder– though some people, no doubt, continue to try their best.

But they also become an object for the creator and a tool that ultimately tells a story that they have no control over; a convenience, a fable. A lot of the time accompanying captions and comments show just how easily the individual can sink below the surface of platitudes and life lessons like ‘never judge a book…’ and ‘we are all one human race’. Is it really imbuing someone with dignity to broadcast their life for another’s gain, even if it is under the guise of ‘art’ or ‘creation’? Sometime the artists themselves can see their intended narrative spiral out of control.

An even more contentious version of the same phenomenon is the filming of homeless people being given money or food by the creator. Again, it can be useful to highlight good deeds and humanise a marginalised group, but can we truly be comfortable as an unsuspecting bystander is immortalised, and consumed into a memorial to the harsh realities of our society.

Granted, the question of how Old Tom Morris would feel about being painted if he had know he would be hanging on the walls of the Kelvingrove as a kind of zany embodiment of provincial life seems a bit inconsequential. But for the modern subjects, who are captured in the much more immediate mediums of photography and video, it seems like a very pertinent consideration to make.

The next day we went to see some more literal memorials. The Glasgow Necropolis is a strange place, if I’m honest. The paths wind breathlessly up a hill, lined with dull stones in a multitude of greys. This is the antithesis of Old Tom Morris saluting the passing museum guests. This is a performance, a most silent and still song and dance.

See the tallest column and largest name and think of me, not as I was or ever could be.

There is no truth to discover, really, because we’re forced to accept their story as it is carved before us. The cloud of sorrow barely dampens the shrill ring of wealth that echoes around the extravagant tombs and statues. But the artifice is also fragile. Another group walks a few feet behind us and laughs at some apparent contradiction chiseled into the stone. Like our painting in reverse, the humanity seeps through the facade. Suddenly the desperation is all around, the human tragedy of monuments built to assert the agency of the dead makes the faces of statues cry.

Memorials are for the living, and those who once lived. More is revealed in the way we react to them than to the things themselves or, obviously, by the people and things they memorialise. Each sacred thing takes a piece of each person who spends a while with it, and that is it’s power.

As we left and headed down toward the cathedral, we walked past a headstone torn in half down the middle like Styrofoam. I felt the sting of sadness and shook my head, as though for them but really for me.

Ultimately, we end up as the interpretations of those we surround ourselves with and those who choose to surround us. It is empowering and debilitating all at once but the contradiction persists at a kind of equilibrium. We should give care to our interpretations, and be sceptical of the lenses through which others are portrayed.

–

From a crowded wall at Kelvingrove

Old Tom Morris beams

Towards the muted audience

Those eyes seem glad to see.

–

“Here you see the everyman

I’ve caught and brought to view.

The meting of his dignity

I will entrust to you.”

–

This is Old Tom’s legacy:

One thump of beating heart.

So, did he know the consequence

Of this shallow part

You wrote for him, then silenced

His laugh with tender strokes,

And turned his face to playing ground

For reflection-seeking folks.

–

That is not Tom Morris,

Who’s collapsing into view.

Tom just holds a mirror up

And takes a piece of you.