The other day I went to Shaw’s Corner. The former residence of Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw; or GBS to his friends (not really). Now I didn’t really know anything about Shaw: I came across him in passing during my undergrad, I knew he wrote Pygmalion, which was adapted into My Fair Lady, but almost nothing else. I was only there because of its proximity to me and my need to try out a new camera, so I went in with an open mind. The house is quite remote, at the end of a series of long, empty roads with blind corners, lined with thick bushes and trees– the fair weather made the journey feel like a summer road trip . You arrive first in the car park, with dusty, crunchy gravel underfoot, a silver food truck and a hut housing all the Bernard Shaw-themed merchandise you could want.

We walked in to the hut and scan our membership cards and left feeling very smug and self-satsfied after being congratulated for having young person’s memberships (for we are the vibrant, promising future of the National Trust). The house itself is obscured by tall hedges along one side of the car park, but once they are rounded the house pops into view. It’s an odd sight. The walls, a reddish-brown brick accented with bright green pipes and window frames, seem to jut out at random and three rooftop chimneys complete its unusual silhouette. It feels like something out of The Hobbit or a Wordsworth poem, the greenery that clings to so much of the walls make it seem like the house itself might have sprouted from the ground.

While the gardens are lovely, it was the inside of the house that I found the most interesting. For the most part it is fairly unspectacular, a big green door opens into a room with off-white walls and framed photos and paintings surround another clutter of off-white doorways that lead to more rooms. The furniture is frail, the decoration old-fashioned with gaudy flower patterns adorning the greenish-white curtains. But one particular decoration really hadn’t aged well. Along the top of one fireplace was a row of photos and drawings: first I noticed a photo of Gandhi… then Lenin, then Stalin. It turns out that Shaw was a dedicated socialist, eugenics enthusiast, dictator admirer and crackpot who thought Hitler should be allowed to escape retribution after WWII and retire to a quiet life in Ireland. It made the old curtains seem positively progressive.

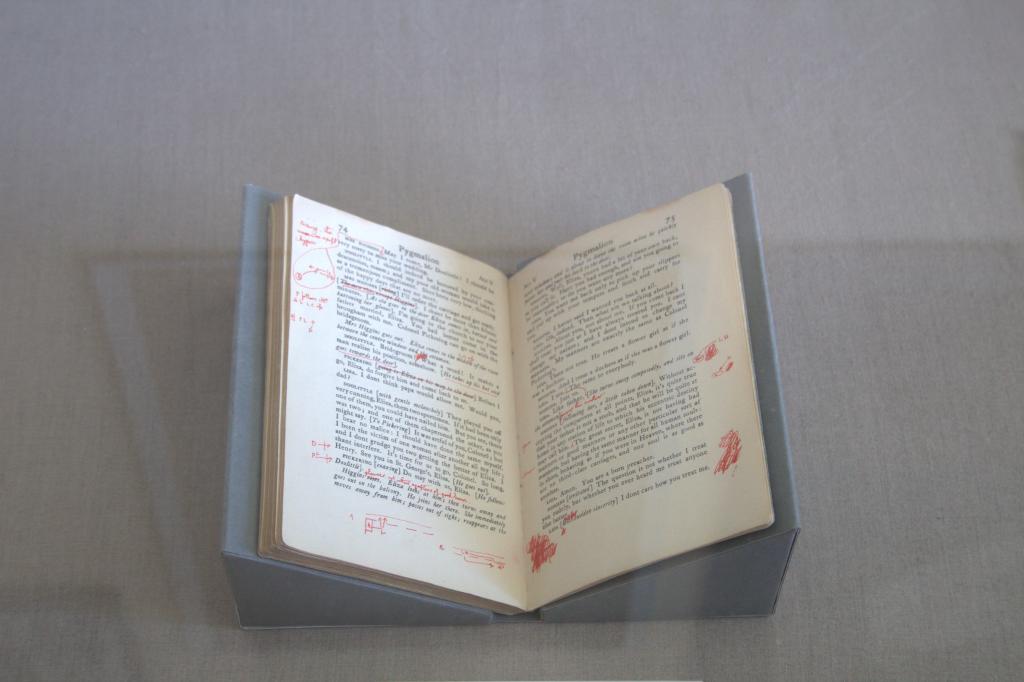

Up the stairs, in the former room of Shaw’s wife Charlotte, was the ‘museum room’. On the wall were flowery quotes and extracts from letters, written by Bernard Shaw. Unfortunately for Charlotte, the letters were not addressed to her but to one “Mrs Pat”. Mrs Patrick Campbell, an actress and socialite, was inspiration for many of Shaw’s characters and, once they began negotiating her appearance as Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion, the two began an intense relationship and exchange of passionate letters. Although Wikipedia tells me it was an ‘unconsummated’ relationship, I’m sure Shaw’s obsessive gushing didn’t please his wife.

The whole thing reminded me of Thomas Hardy who developed similar infatuations with female acquaintances. Florence Henniker, a writer with whom Hardy eventually collaborated, was forced to reject his romantic advances (despite his being married at the time), although was later used as inspiration for Sue in his final novel Jude the Obscure.

Later in life, the actress Gertrude Bugler became an object of interest for the now eighty-year-old Hardy as she played the leading roles in the stage adaptations of many of his novels. This time, when Gertrude was due to star in Tess of the D’Urbervilles in London, Hardy’s second wife gave in to her jealousy and refused to allow it. While I don’t have Thomas Hardy posters on my wall or drift off to sleep listening to his poetry, it leaves a slightly bitter taste when someone who’s work you admire has their raw, unfiltered character revealed to you.

All this made me think of how we deal with the complexity of our cultural heroes. George Bernard Shaw is undoubtedly significant, his work should be read and not thrown out along with his troubling personal philosophies. I am glad that the photo of Stalin remains on the fireplace as a record of Shaw’s reality, but it seems to be just an inconvenient footnote attached to a monument to his brilliance. And I concede that the house may exist as just a snapshot of a famous person’s life for posterity but the National Trust website just delivers a watered down version of Shaw’s socialism that feels a bit intellectually insincere; a way to justify the celebration of the man. But it has to be possible for people to exist both as venerated celebrity and flawed human.

In the social media-influenced dialogue, however, it seems that there is a shrinking space for complexity and nuance. I think ‘Cancel Culture’, perhaps rather controversially, can be a useful phenomenon… sometimes. When a public figure’s reputation is so concretely positive and elevated, it can take a collective effort to pierce the facade of perfection. But, in a sphere where everyone craves clickable, shareable and digestible opinions, people must be heroes or villains– and the distance between those two states seems to be shrinking.

In the current climate, this piece could be considered a concrete cancellation of George Bernard Shaw, and the National Trust’s literary hero becomes a villain. But I think really it is just unveiling another aspect of a messy, human life and, while it takes more effort to untangle appreciation for achievements from dogma and ideology, it makes for a far more interesting story. Surely Winston Churchill can be both a white supremacist and unalterable enmeshed with the story of Allied victory in WWII and any complete deification or vilification is unhelpful. But perhaps those who were made victims at his hands would rightly call out my insistence on balance and nuance.

I don’t know what the right answer is but what I have decided for myself is that not only should you not meet your heroes, you shouldn’t make them in the first place. And as we were leaving Shaw’s Corner, we went up to the silver food truck and bought a couple of drinks. While the girl was grabbing them she told us about Shaw’s office in the gardens outside the house. ‘It rotates so he could face the sun whenever he wanted, ‘ she told us, ‘and he called it London, so his housekeeper could tell unwanted guests that he was away in the capital’. I chuckled thinking about the clever system and decided perhaps one should not meet their villains, either.